Monday, August 28, 2023

Sunday, August 20, 2023

Tuesday, August 15, 2023

Celera 500L: The World's Most Fuel Efficient Airplane

|

| Celera 500L patent illustration (Credit William M. Otto, Otto Aviation Group) |

General characteristics

- Capacity: 6 passengers

- Cabin height: 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m)

- Cabin volume: 448 cu ft (12.7 m3)

- Powerplant: 1 × AO3 RED diesel piston engine, 550 hp (410 kW) approximate at takeoff

Performance

- Cruise speed: 400 kn (460 mph, 740 km/h) estimated minimum

- Range: 4,500 nmi (5,200 mi, 8,300 km)

- Service ceiling: 30,000 ft (9,100 m)

- Maximum glide ratio: 22:1

- Fuel economy: 18–25 mpg‑US (13.1–9.4 L/100 km)

Links and References

Otto Celera 500L

The Celera 500L Just May Revolutionize Business Aviation

Future of flying: Introducing the new Otto Celera 500L aircraft

World's most efficient passenger plane gets hydrogen powertrain

Utilizing Renewable Methanol to Power Electric Commuter Aircraft

Wednesday, August 9, 2023

SLS Derived Artificial Gravity Habitats for Orbital Havens and Interplanetary Space Travel

Notional spinning artificial gravity producing AGH 1500 orbiting 600 km above the Earth's surface. Rectractable solar arrays and radiators produce power and regulate temperatures for the twin habitats.

by Marcel F. Williams

Microgravity environments are inherently deleterious to human health in space.

Weight loss, the clumping of perspiration and tears, facial and speech distortions,

a degraded sense of taste and smell, and even an increased frequency of flatulence are minor problems associated with short term exposure to a microgravity environment.

But months or years under microgravity conditions can cause much more serious problems for human health in space. Without regular exercise, 20% of muscle mass can be lost in just 12 days. 1.5% of bone mass is lost in a single month. And this bone demineralization can increase the calcium concentration in the blood stream, increasing the risk of developing kidney stones. Significant

reductions in cardiovascular fitness can also result from long periods

of microgravity conditions. Vision problems of varying degrees of

severity can occur in men in their 40s or older. And the use of

medicine can be hampered due to the changes in blood flow redistribution

under microgravity conditions.

After a few months aboard the ISS, the blood

pressure of some astronauts drops to abnormally low levels when they move from a

lying position to a sitting or standing position. Some astronauts even

have problems standing up, walking, and turning and stabilizing their

gaze.

The deployment of small habitats that are capable of spinning to produce artificial gravity could alleviate the health problems associated with a microgravity environment. Artificial gravity habitats could allow humans to:

1. Remain in orbit perpetually without the need to return to the Earth’s

surface reducing the number of launches necessary to maintain a human

presence in space

2. Remain physically healthy during long interplanetary journeys

3. Receive quality medical care while in orbit including major surgical procedures.

4. Have a permanent human presence in orbit practically anywhere in the solar system

5. Test variable levels of gravity on the health of humans and other animal species

|

| Notional 10 meter in diameter AGH 1500 in launch configuration on top of the SLS compared an SLS vehicle with an EUS and 10 meter in diameter payload faring. |

An SLS Block I configuration would easily be capable of deploying a 60 tonne artificial gravity habitat to LEO. Reusable EUS derived ROTV 100 orbital transfer vehicles cold to deploy the habitat to the appropriate orbit where thrusters could rotate the structure, expanding its twin counter balancing pressurized habitats at the ends of a 224 meter in diameter boom.

Directly derived from the SLS oxygen tank architecture, each habitat would be

8.4 meters wide and 16.8 meters tall. This would allow at least five 8.4 meter in diameter habitat levels that are at

least 2.5 meters high, ten human habitat levels in total for the habitat. This should be

enough room to easily accommodate 12 to 32 astronauts and their guest within the twin

counter balancing pressurized modules. Because the combined pressurized area of the twin habitat modules exceeds 1500 cubic meters in volume, the notional artificial gravity habitat is here referred to as the: AGH 1500 (Artificial Gravity Habitat 1500).

|

| AGH 1500 both contracted for trajectory burns and expanded to rotate producing 0.5g of simulated gravity |

In

order to mitigate the physiological effects of Coriolis, the habitat

would be approximately 224 meters in diameter, rotating at approximately

2rpm (two rotations per minute) to produce 0.5g of simulated gravity

(higher than the

gravity on the Moon and Mars). Slower rotations could be used to simulate the gravity on the Moon, Mars, Mercury, and Callisto, low gravity worlds that could potentially be colonized by humans someday.

Housed

within a ten meter external cylinder would create a 80 centimeter gap

between the pressurized habitat. Less than 20 centimeters of water

within an external polyethylene bag or pipes could provide astronauts

on interplanetary journeys with protection against the heavy nuclei

component of cosmic radiation and from major solar storm events while

also reducing cosmic radiation exposure in general during multi-month

interplanetary journeys.

Permanent

artificial gravity habitats located beyond the magnetosphere within

cis-lunar space and in orbit around other planets, moons, and asteroids

will have to be provided with much more shielding to protect against

excessive radiation exposure and potential micrometeorite damage. About 2

meters of lunar regolith would be required to shield the the

pressurized habitat. But less than 80 centimeters of space would be

available. However, lunar regolith is rich in much denser iron particles

that could be mined and deployed for external shielding. So only 40

centimeters of lunar iron could be used to permanently shield artificial

gravity habitats. Thorium is an even denser lunar material could also

be utilized since there appears to be substantial thorium deposits in

certain regions on the Moon.

|

| SLS EUS (Exploration Upper Stage) next to a notional EUS derived ROTV 100 (Reusable Orbital Transfer Vehicle +100 tonnes of propellant) |

The

telescopic boom cylinders are approximately 5 millimeters thick (much

thicker that the fuselage for an airplane). Five cylindrical booms

would be housed within the ten meter in diameter cylinder that

accommodates radiation and micrometeorites shielding before the booms are expanded. One centimeter

would be added to the top of each cylinder in order for each segment of

the boom to securely attach to each other. So 1.5 centimeters would be

required for each cylinder. Plus you have to add a centimeter for the

boom cable that allows the boom to expand and contract. So ten

centimeters would have to be utilized for the telescopic boom. That

would allow nearly 70 meters to be used for radiation and micrometeorite shielding. But, as previously stated,

only 40 meters or less would be required to permanently shield the twin habitat modules.

|

| AGH 1500 being deployed to a low Earth orbit 600 km above the Earth's surface by an EUS derivied reusable ROTV-100 |

Reusable EUS derived ROTV 100 vehicles could deploy the AGH 1500 600 kilometers to mitigate frictional drag from the Earth's atmosphere. After refueling at LOX/LH2 propellant depots, two ROTV 100 orbital transfer vehicles could deploy the AGH 1500 to various locations within cis-lunar space: NRHO, DRO, L3, L4, and L5. And twin ROTV orbital transfer vehicles could also deploy the AGH 1500 from cis-lunar space to the orbits of Mars and Venus-- allowing a permanent human presence in orbit above the surface of Mars and the clouds of Venus.

|

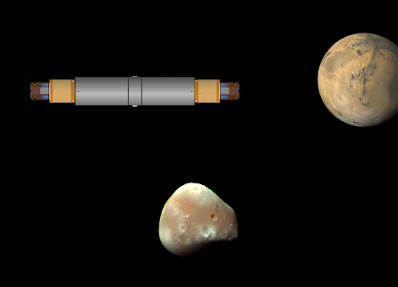

| Twin ROTV 100 orbital transfer vehicles deploy an AGH 1500 from lunar orbit to a high Mars orbit beyond the orbit of the martian moon, Deimos |

Links and References